Before starting or approving any major activity or an event, it is important to see and verify that they are in right position to begin with. Only a few people remember everything and others have to refer and what they have to refer is a Checklist.

A checklist is a type of job aid used to reduce failure by compensating for potential limits of human memory and attention. It helps to ensure consistency and completeness in carrying out a task.

First you write a todo list then you work on completing each task in the list and check it off and finally when you review the list and see everything is done, you are good to go. Its that simple, actually its not. Sometimes we don’t we have this todo list in a paper or device, we mostly try to keep it in memory thats the problem.

Todo list is not a checklist but they both have to be synchronized. A todo list could be a sequence of event(SoE) or a list of tasks that can be sorted by priority or time. Checklist is a list for verifying whether the tasks been completed.

Two examples i have come across on “why checklists are important”

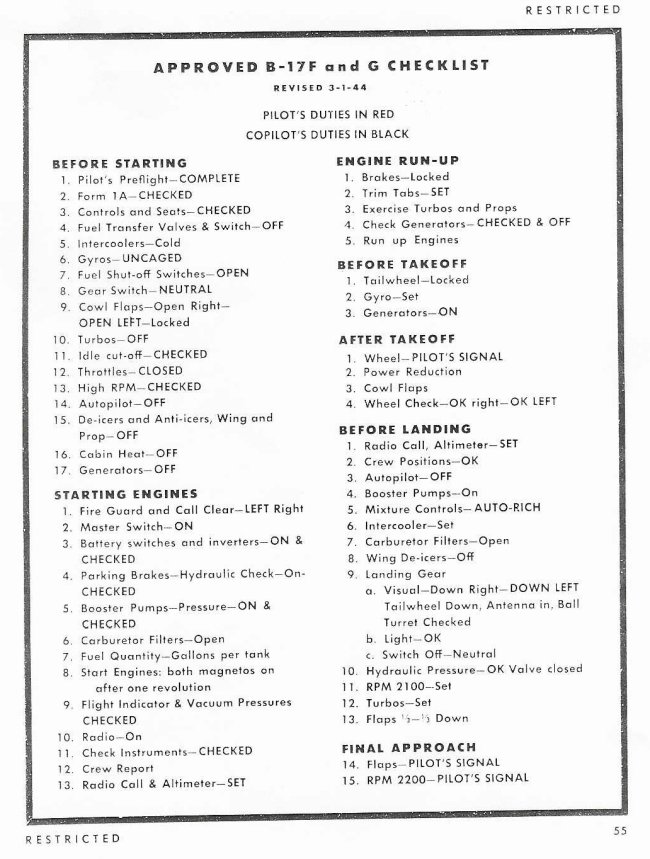

# Boeing was about to crash in 1930 after B-17 crashed

In 1930s, boeing B-17 crashed as aircraft stalled shortly after takeoff and crew were seriously injured and some died and the company was about to collapse. After this incident, B-17 was considered as a “too much airplane for one man to fly” as it involved so many steps and pilots can easily forget something important. Investigation revealed,

- Captain had left the elevator lock on

- aircraft was unresponsive to pitch control

Boeing conducted a think-tank session and concluded pilots need a checklist. Checklist isn’t a challenge to pilots skills or aircraft too hard to fly, its just too hard to keep it all in memory.

By implementing the checklists, they flew 1.8 million hours with 18 B-17s without incident, proved to the government they were safe and viewed as practically crash-proof and govt eventually ordered for nearly 13,000 B-17s.

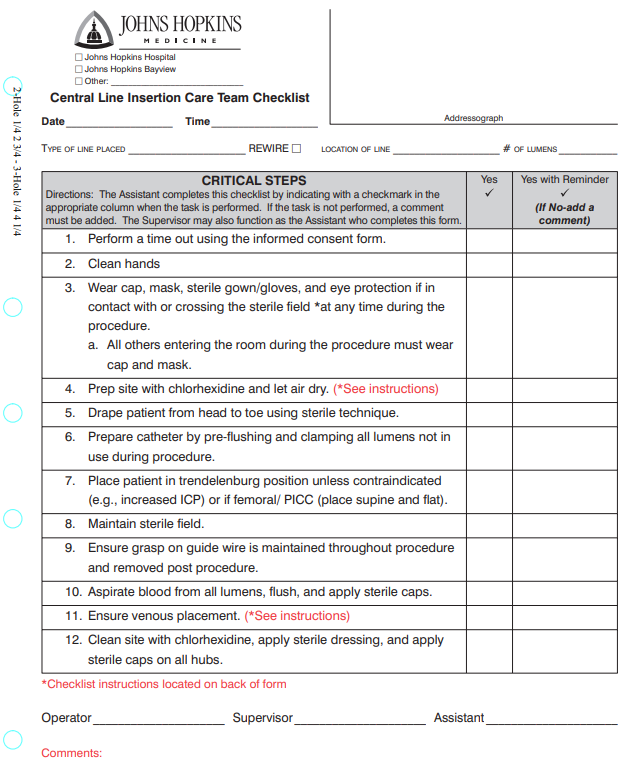

# Hospital checklist to improve the health care outcomes

A central venous catheter is, in many ways, an amazing medical innovation— but it took insights from the social sciences, not the medical sciences, to make it safe to use. The catheter, known informally as a central line, is a narrow tube inserted into a large vein, which allows doctors to deliver drugs and fluids rapidly to a patient in the intensive care unit, where every minute counts. But central lines can get infected, and when that happens, they can be conduits for bacteria or fungi to go straight into the bloodstream, causing sepsis, organ failure, and even death.

Physicians have long considered lethal infections to be an inevitable risk of central lines. But these are not small risks. According to surgeon and author Atul Gawande, about 4 percent of central venous catheters become infected every year, involving about 80,000 patients.1 These infections, he writes, are expensive to treat and are fatal up to 28 percent of the time, “depending on how sick one is at the start.” If an innovation could be found to lower those rates, the impact on both quality of life and health care costs would be huge. It would also represent a significant step in medical progress—and, just possibly, in non-medical settings as well.

Peter Pronovost, a critical-care specialist at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, thought of central line infections not as an inevitable risk but as a problem to be solved. When Pronovost asked the ICU nurses at Hopkins to observe central line insertion carefully, it turned out that in one case out of three, the doctor skipped at least one of these essential steps.

In the early 2000s it occurred to him that if just a few steps were followed every time a central line was inserted, the prevailing narrative about central line infections could be changed from “these infections are inevitable” to “they can and must be prevented.”

He worked up a checklist of five safety routines to be run through every time a catheter was inserted:

- wash your hands with soap

- clean the patient’s skin with a specific antiseptic

- put sterile drapes over the entire patient (not just the immediate area around the catheter)

- wear sterile gear (mask, hat, gown, gloves)

- and put a sterile dressing over the catheter site after the line is inserted

He gave the ICU nurses instructions to run through the checklist before each central line insertion and to insist doctors follow each step. Next—and this part was crucial—he got hospital administrators to back up the nurses if the doctors balked at this disruption of the traditional medical hierarchy. He also employed some basic time management strategies, making sure that all the supplies needed for safe central line insertion—the full-body drapes, the sterile gowns and masks, the chlorhexidine soap—were assembled in one place in a central venous catheter kit

Above two are great examples to remind me why checklists are important

90% of the time, the checklists are same, when you compare it to the same department in different companies, sector or fields and only 10% differs. That 10% is something unique to that company or enterprise that makes it outstanding, you can say.

Behind every checklist item, there is a failure story, ask for it.