Secrets of Successful Project Management by Karl Wiegers

— IT-skills — 8 min read

Below article is not written by me, but i found it accidently and the article is very good. I am copying it here, so that i can refer to it or read later. Check references for author details.

This is from Medium article Secrets of Successful Project Management. Below is not the complete article, just the part i found interesting. I have no experience at this point in project management, but sort of feel, each of the point is logical and should be actioned.

Laying the Foundation

1. Define project success criteria

At the beginning of the project, make sure the key stakeholders share a common understanding of how they’ll determine whether this project is successful. Begin by identifying your stakeholders and their interests and expectations. Next, define some clear and measurable business goals. Some examples are:

- Increasing market share by a certain amount by a specified date

- Reaching a specified sales volume or revenue

- Achieving certain customer satisfaction measures

- Saving money by retiring a high-maintenance legacy system

- Achieving a particular transaction processing volume and accuracy

Besides these goals, keep your eye on team member job satisfaction. This is sometimes indicated by staff turnover rate and the willingness of team members to do what it takes to make the project succeed.

If you don’t define clear priorities for success, team members can work at cross-purposes, leading to frustration, stress, and reduced effectiveness.

2. Identify project drivers, constraints, and degrees of freedom.

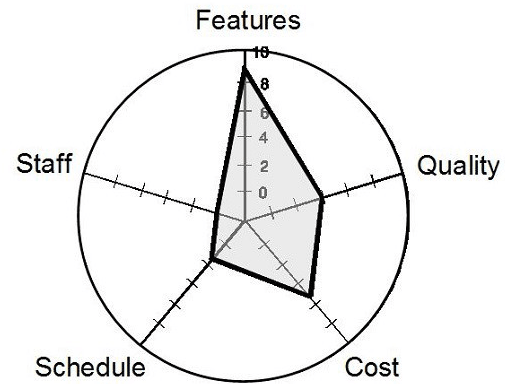

Every project must balance its functionality, staffing, cost, schedule, and quality objectives. Define each of these five project dimensions as either a constraint within which you must operate, a driver strongly aligned with project success, or a degree of freedom you can adjust within some stated bounds.

The smaller the area inside the pentagon, the more constrained the project is. A flexibility diagram for a project that is staff-constrained and schedule-constrained, with cost being a driver, and quality and features being degrees of freedom.

I once heard a senior manager ask a project leader how long it would take to deliver a planned new large software system. The project leader replied, “Two years.” The senior manager said, “No, that’s too long. I need it in six months.” The project leader’s response was simply, “Okay,” despite the fact that nothing had changed in the few seconds of that conversation to make the six-month target achievable. A better response would have been to negotiate a realistic outcome through a series of questions:

- How critical is the six-month target? Does something drastic happen if we don’t deliver in six months (schedule is a constraint), or is that just a desirable target date (schedule is a driver)?

- If the six months is firm, what subset of the requested functionality do you absolutely need delivered by then? (schedule is a constraint, functionality is a driver)

- Can I get more people to work on it? (staff is a degree of freedom)

- Do you care how well it works? (quality is a degree of freedom)

3. Define product release criteria.

Early in the project, decide what criteria will indicate whether the product is ready for release. Here are some examples of release criteria:

- There are no open high-priority defects.

- The number of open defects has decreased for X weeks and the estimated number of residual defects is acceptable.

- Performance goals are achieved on all target platforms.

- Specific required functionality is fully operational.

- Quantitative reliability goals are satisfied.

- X% of system tests have been passed.

- Specified legal, contractual, or regulatory goals are met.

- Specified customer acceptance criteria are satisfied.

- The optimum marketplace time to release has arrived.

4. Negotiate achievable commitments

Despite pressure to promise the impossible, never make a commitment you know you can’t keep. Engage in good-faith negotiations with customers, managers, and team members about goals that are realistically achievable. Negotiation is required whenever there is a gap between the schedule or functionality the key project stakeholders demand and your best prediction of the future as embodied in project estimates.

- Principled negotiation involves four precepts:

- Separate the people from the problem.

- Focus on interests, not positions.

- Invent options for mutual gain.

- Insist on using objective criteria.

Any data you have from previous projects will help you make persuasive arguments, although there is no real defense against truly unreasonable people.

Certain senior managers can have a target date to achieve a specific goal and it might be a pure fantasy. Only after careful evaluation you can say "I’m not going to commit to that goal".

Planning the project

5. Write a plan

This one seems obvious. But some people believe the time spent writing a plan could be better spent writing code. I don’t agree. The hard part isn’t writing the plan. The hard part is really doing the planning — thinking, negotiating, balancing, asking, listening, and then thinking some more. Actually writing the plan is mostly transcription at that point. Multi-site and cross-cultural development projects demand even more careful planning and tracking than do projects with a co-located team.

A useful plan is much more than a schedule or work breakdown structure of tasks to perform. It also includes:

- Staff, budget, and other resource estimates and plans

- Team roles and responsibilities

- How you will acquire and train the necessary staff

- Assumptions, dependencies, and risks

- Descriptions of, and target dates for, major deliverables

- Identification of the development life cycle that you’ll follow

- How you will track and monitor the project

- Metrics and other data that you’ll collect

- How you will manage any subcontractor relationships

- Your organization should adopt a standard project management plan template, which can be tailored for various kinds of projects.

Avoid overburdening small projects with excessive documentation that adds little value.

6. Decompose tasks to inch-pebble granularity

Breaking large tasks into multiple small tasks helps you estimate them more accurately, reveals work activities you might not have thought of otherwise, and permits more accurate, fine-grained status tracking. I feel most comfortable with inch-pebbles that represent tasks of about 5 to 15 labor-hours, or about one to three days in duration. Overlooked tasks are a common contributor to schedule slips, so breaking large problems into small bits reveals more details about the work that must be done and improves your ability to make accurate estimates.

7. Develop planning worksheets for common large tasks

For frequently performed tasks, have a activity checklist. No single person will think of all the necessary tasks, so engage multiple team members in developing these worksheets. Using standard worksheets will help the team members adopt common processes that they can tune up as they gain experience. Tailor the worksheets to meet the specific needs of individual projects.

8. Plan to do rework after a quality control activity

Almost all quality control activities (testing, peer reviews, and the like) reveal defects or other improvement opportunities. Include rework as a discrete task after every quality control activity in your project schedule or work breakdown structure.

9. Manage project risks

If you don’t identify and control your project’s risks, they will control you. A risk is a potential problem that could affect the success of your project, a problem that hasn’t happened yet — and you’d like to keep it that way. Risk management is one of the most significant best practices for software development. Simply identifying the possible risk factors isn’t enough. You also have to evaluate the relative threat each one poses so you can focus your risk management energy where it will do the most good. Risk exposure is a combination of the probability that a specific risk could materialize into a problem and the negative consequences for the project if it does.

10. Plan time for process improvement

Your team members are already swamped with their current project assignments. But if you want the group to rise to a higher plane of software engineering capability, you’ll have to invest some time in process improvement. Don’t allocate 100 percent of your team members’ available time to project tasks and then wonder why they don’t make any progress on the improvement initiatives.

11. Respect the learning curve

The time and money you spend on training, reading and self-study, consultants, and developing improved processes are part of the investment your organization makes in project success. Recognize that you’ll pay a price in terms of a short-term productivity loss when you first try to apply new processes, tools, or technologies. Don’t expect to get fabulous benefits from new approaches on the first try, no matter what the tool vendor or methodology consultant claims. Instead, build some extra time into the schedule to account for the inevitable learning curve. Make sure your managers and customers understand the learning curve and accept it as an inescapable consequence of working in a rapidly changing field.

Estimating the work

12. Estimate based on effort, not calendar time

People generally provide estimates in units of calendar time. I prefer to estimate the effort (in labor-hours) associated with a task, and then translate the effort into a calendar-time estimate. A 20-hour task might take 2.5 calendar days of nominal full-time effort, or 2 exhausting days.

13. Don’t schedule multitasking people for more than 80 percent of their time

Excessive multitasking introduces communication and thought process inefficiencies that reduce individual productivity.

14. Build training time into the schedule

Heading says it all. Incorporate training time into project schedule.

15. Record estimates and how you derived them

When you prepare estimates for your work, write down those estimates and document how you arrived at each of them. Understanding the assumptions and approaches used to create an estimate will make them easier to defend and adjust when necessary. It will also help you improve your estimation process. Develop estimation procedures and checklists that people throughout your organization can use.

16. Use estimation tools

Numerous commercial tools are available to help you estimate costs and schedules for entire projects.

17. Plan contingency buffers

We all know that projects never go precisely as planned. The prudent project manager incorporates budget and schedule contingency buffers (also known as management reserve) at the end of major phases to accommodate the unforeseen. Use your project risk analysis to estimate the possible schedule impact if several of the risks materialize and build that projected risk exposure into your schedule as a contingency buffer. Even more sophisticated is the use of critical chain analysis, a technique that pools the uncertainties in estimates and risks into a rational overall contingency buffer.

Tracking progress and Learning for the future

18. Record estimates and actual outcomes

Unless you record the actual effort or time spent on each task and compare them to your estimates, you’ll never improve your estimating approach. Your estimates will forever remain guesses. Each individual can begin recording estimates and actuals for their own work, and the project manager should track these important data items on a project task or milestone basis.

In addition to effort, cost, and schedule performance, you could estimate and track the size of the product if this is valuable to you like number of requirements, lines of code, function points, classes and methods, user interface screens, and story points.

19. Count tasks as complete only when they’re 100 percent complete

Your project status tracking is then based on the fraction of the tasks that are completed, not the percent completion of each task. If someone asks you whether a specific task is complete and your reply is, “It’s all done except…”, then it’s not done! Don’t let people round up their task completion status. Instead, use explicit criteria to tell whether a step truly is completed.

20. Track project status openly and honestly

The painful problems arise when you don’t know just how far behind (or, occasionally, ahead) of plan the project really is. Strive to run the project from a foundation of accurate, data-based facts, rather than from the misleading optimism that sometimes arises from the fear of reporting bad news. Use project status information and metrics data to take corrective actions when necessary and to celebrate when you can. You can only manage a project effectively when you really know what’s done and what isn’t, what tasks are falling behind their estimates and why, and what problems and issues remain to be tackled.

21. Conduct project retrospectives and record lessons learned

Retrospectives (also called postmortems, debriefings, and post-project reviews) provide an opportunity for the team to reflect on how the last project or the previous phase went and to capture lessons learned that will help enhance your future performance. During such a review, identify the things that went well, so you can create an environment that enables you to repeat those success contributors. Also look for things that didn’t go so well, so you can change your approaches and prevent those problems in the future. In addition, think of events that surprised you. These might be risk factors to watch out for on the next project.